Facing both renewed risks of recession but also still stubbornly high inflation, the policy dilemma facing this week’s BoE MPC meeting is even more stark than ever. In August, only one dove, Swati Dhingra, broke ranks to vote against what turned out to be a remarkable fourteenth successive tightening and two of the most hawkish participants, Jonathan Haskel and Catherine Mann, even wanted a larger 50 basis point hike. Mann still seems to favour another hike but other recent comments have suggested that an increasing number of MPC members have become more concerned about the danger of raising Bank Rate too far. Not surprisingly therefore, forecasters are much more uncertain about Thursday’s outcome than for quite some time. That said, the market consensus is another 25 basis point increase in the benchmark rate to 5.50 percent which, if correct, would match its highest level since July 2007 and bring the cumulative tightening since December 2021 to some 540 basis points.

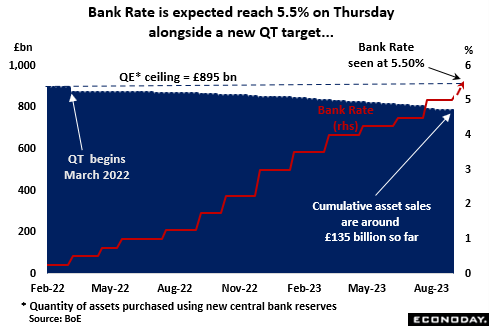

Meantime, apart from the temporary emergency U-turn prompted by last September’s disastrous mini-budget, the QT programme has run well and smoothly enough that planned gilt disposals this month have had to be trimmed to prevent them from overshooting the full year target (by £80 billion to £758 billion). In early September, disposals stood at just over £115 billion which, combined with the £20 billion of corporate bond sales already completed, put the total reduction in the balance sheet at about £135 billion since February 2022. The new target for the coming 12 months is expected to be announced alongside the interest rate decision on Thursday. Any change in the planned pace of sales could be read as a subtle shift in the overall policy stance, albeit clearly much less so than any move on interest rates.

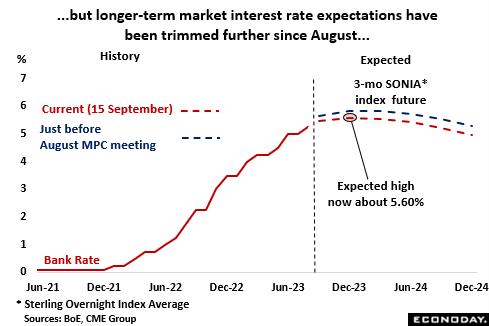

Financial markets have continued to trim their interest rate expectations since the August MPC meeting. At that time, 3-month money rates were seen peaking next March at around 5.85 percent. However, futures prices now see the top at 5.60 percent in December and also anticipate a faster decline to just below 5.00 percent by the end of next year.

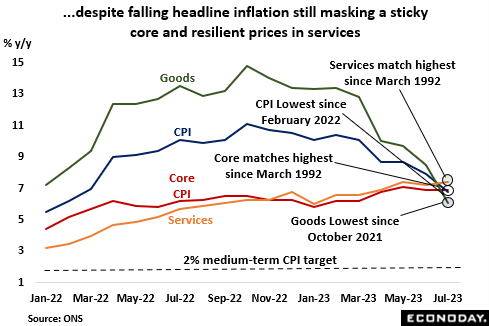

Headline inflation declined in July by more than a full percentage point to 6.8 percent, its lowest level since March 2022. However, the drop was largely due to the reduction in the energy price cap imposed by the Office of Gas and Electricity Markets (Ofgem). More importantly, the rate in services – a big worry for the BoE – accelerated to 7.4 percent, matching its highest mark since March 1992. Core inflation was little better; holding steady at June’s 6.9 percent post, itself the second strongest print in more than 31 years. In other words, underlying inflation is both far too high and, seemingly, not even moving in the right direction. Wednesday’s August CPI report will update the inflation picture but is unlikely to be decisive in either direction. In any event, a worry for the bank will be its new inflation expectations survey released last Friday. This showed increases in the rates for both 1-year ahead (3.6 percent after 3.5 percent) and 3-years ahead (2.8 percent after 2.6 percent).

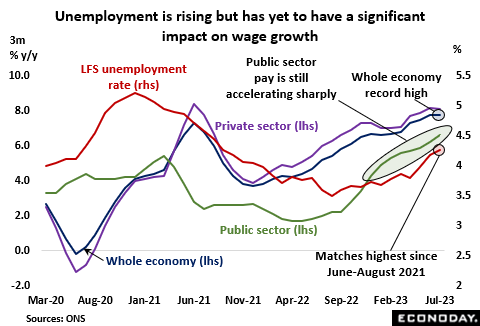

Meantime, while the signs are that higher interest rates are cooling the labour market, rising unemployment has yet to have much impact on wages. At 8.5 percent in the three months to July, headline annual weekly earnings growth was just 0.4 percentage points short of the Covid-distorted 8.9 percent all-time high seen in the second quarter of 2021. Indeed, the 7.8 percent rate posted by regular wages matched April-June’s record peak. The private sector has shown some signs of topping out but public sector pay rises have been especially strong. To this end, the bank is watching for any indications that the usual link between pay rises for new hires and those for workers more broadly have broken down. If so, recent evidence of a slowdown in starting pay growth might not point to an imminent deceleration in overall earnings. In any event, current pay rates remain incompatible with achieving the inflation target on a sustainable basis.

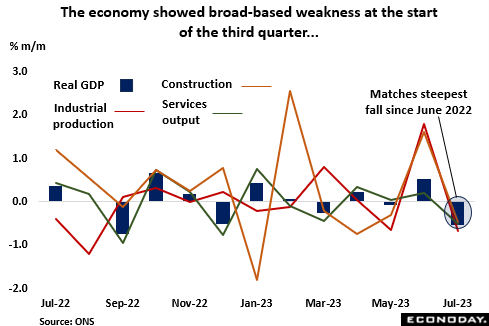

More generally, the chances that the economy will suffer at least one quarter of negative growth before year-end have increased. Bank holiday-related distortions have added to the volatility of recent monthly data but, even allowing for bad weather and more industrial action, a broad-based 0.5 percent slump in July provided an ominously poor start by GDP to the current quarter. The downswing in manufacturing appears to be over the worst and not as deep as some surveys foresaw but the key services category, which had been instrumental in keeping total output on a modestly rising trend, posted its first drop in July since March. Rising borrowing costs (particularly in the housing market) and still high inflation may now be more fully taking their toll. When combined with soft overseas markets – excluding precious metals, export volumes have fallen in each of the last three quarters – this suggests overall demand could be a sizeable drag on output over coming months.

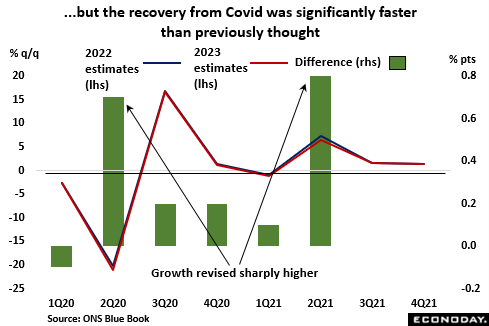

Still, the MPC hawks can point to the recovery from the pandemic being markedly stronger than originally thought. The bank has freely acknowledged significant difficulties trying to model how the economy has performed since the advent of Covid and its understanding may have been further clouded by the revisions to the national accounts announced earlier this month. Previously, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) had reported that real GDP at the end of 2021 was 1.2 percent below its level in the fourth quarter of 2019, the last full quarter before the pandemic hit. However, total output is now thought to have been 0.6 percent higher. Indeed, as recently as August the official line was that the economy was still 0.2 percent smaller than just before Covid arrived. The upward revision may help to explain why the labour market has stayed so tight for so long, a phenomenon that the bank has struggled to explain. Either way, the magnitude of the revisions will have done nothing to improve the bank’s already shaky confidence in the ONS data.

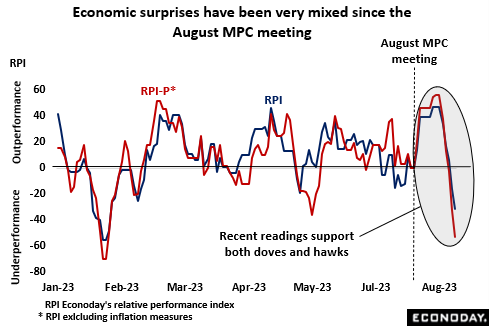

From a market perspective, economic news has been very mixed since the beginning of August, adding to the uncertainty about Thursday’s vote. At 9, Econoday’s relative performance index (RPI), which measures how the overall economy has recently fared versus market expectations, shows a very limited degree of outperformance. However, since the August MPC meeting, the gauge has swung sharply in both directions to provide ammunition for doves and hawks alike.

In a nutshell, the bank this week probably has to choose between raising rates now with the carrot of earlier reductions in 2024 or holding steady and maintaining current levels for that much longer. Crucial will be the extent to which MPC members believe the impact of the previous 14 monetary tightenings has still to feed through. Even should the vote be clear-cut; the complex economic picture means that few MPC members are likely to be fully convinced that they are doing the right thing. As such, if rates do go up, the impact could be partially diminished by a more dovish policy statement.

Econoday’s Global Economics articles detail the results of each week’s key economic events and offer consensus forecasts for what’s ahead in the coming week. Global Economics is sent via email on Friday Evenings.

Econoday’s Global Economics articles detail the results of each week’s key economic events and offer consensus forecasts for what’s ahead in the coming week. Global Economics is sent via email on Friday Evenings. The Daily Global Economic Review is a daily snapshot of economic events and analysis designed to keep you informed with timely and relevant information. Delivered directly to your inbox at 5:30pm ET each market day.

The Daily Global Economic Review is a daily snapshot of economic events and analysis designed to keep you informed with timely and relevant information. Delivered directly to your inbox at 5:30pm ET each market day. Stay ahead in 2025 with the Econoday Economic Journal! Packed with a comprehensive calendar of key economic events, expert insights, and daily planning tools, it’s the perfect resource for investors, students, and decision-makers.

Stay ahead in 2025 with the Econoday Economic Journal! Packed with a comprehensive calendar of key economic events, expert insights, and daily planning tools, it’s the perfect resource for investors, students, and decision-makers.