Not for the first time, the SNB surprised investors at its September’s Monetary Policy Assessment (MPA) when it announced no change to its policy rate. Despite some earlier hawkish rhetoric, a downward revision to the central bank’s inflation forecast combined with a deteriorating economic outlook proved enough to convince the monetary authority that its stance was already tight enough. That said, the bank was also at pains to point out that the door to higher interest rates was still open and just a few weeks ago Vice Chairman Martin Schlegel was warning that inflation pressure was still elevated. Nonetheless, recent economic developments have left speculators fairly certain that the December MPA will also maintain the status quo, meaning that the policy rate stays at 1.75 percent, its highest mark in 15 years.

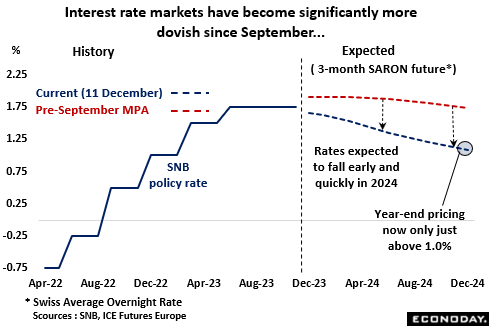

In fact, interest rate expectations in financial markets have been trimmed significantly since September. Just before the last MPA, futures were pricing in a peak to 3-month rates of around 1.90 percent and saw only limited downside potential in 2024. However, now the SNB is seen cutting as soon as March with rates continuing to decline to almost 1.0 percent by the end of next year. Such a view is likely to be far too aggressive for the central bank at this stage.

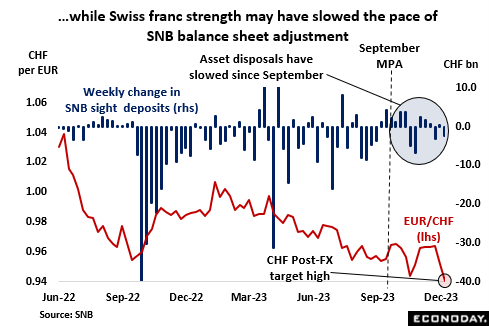

An already very strong Swiss franc was given an additional boost in October by safe haven flows associated with the heightened tensions in the Middle East. Indeed, at CHF0.94087 just last Thursday, the unit posted its firmest level against the euro since the SNB pulled the plug on its target floor back in January 2015. While accepting that a robust currency has helped to bring inflation back under control, the central bank has also stressed the importance of FX stability and it may be that the unit’s rise was seen as too steep. Current levels are probably about as firm as the SNB wants to see and may be one reason why the pace of asset sales aimed at shrinking the bank’s balance sheet has slowed in recent months.

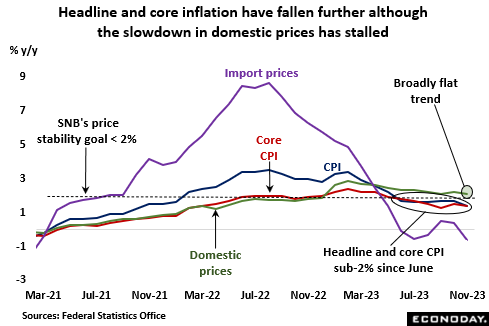

Inflation news since the last MPA has been generally favourable. Both the annual headline and core CPI rates were just 1.4 percent in November, and so well below the SNB’s near-2 percent target. In fact, both gauges have been consistently short of that mark since June. The bank will have noted the recent relative stickiness of domestic prices (2.1 percent) but further up the pipeline, pressures have also eased. The yearly change in the combined producer and import price index has been negative for six months now and, in October, the core measure went sub-zero for the first time since April 2021. With wage growth generally expected to ease in 2024 and absent a new commodity price shock, inflation developments seem unlikely to be a significant policy issue over coming months.

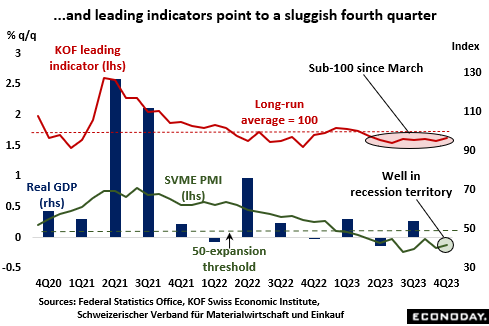

Having dipped in the previous period, the economy unexpectedly expanded in the third quarter. However, a 0.3 percent increase in total output was driven by net foreign trade. Final domestic demand was only flat having already fallen 0.5 percent in April-June. Household consumption, which rose a modest 0.2 percent, continues to be supported by ongoing, if slowing, gains in employment but fixed capital formation fell again. A 0.7 percent decrease was its third drop in the last four quarters, leaving investment at its weakest level since the first quarter of 2021 and potentially posing a downside risk to supply.

Leading indicators from the KOF and SVME remain well below their historic norms but have at least strengthened over the last couple of months. Declining order books probably rule out any near-term recovery in manufacturing but service sector activity has been growing modestly since August. Rising new orders and backlogs here mean that while a recession is possible, it is unlikely in the absence of another commodity price shock.

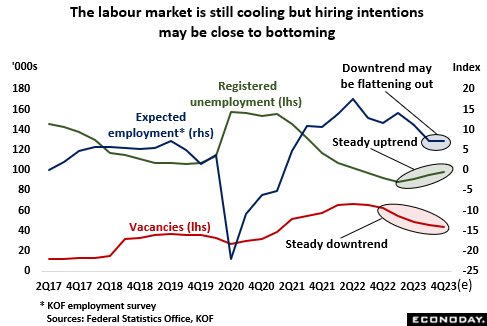

Crucially for the SNB, the labour market is cooling. Unemployment has risen every month since February and, as of October, vacancies were down fully 27 percent on the year. Nonetheless, the jobless rate and concerns about job security remain historically low and, outside of manufacturing, the KOF’s fourth quarter employment survey found businesses still planning to add to headcount. Against this backdrop, the market is still tight and the SNB will be all the more cautious about taking its foot off the monetary brake too soon.

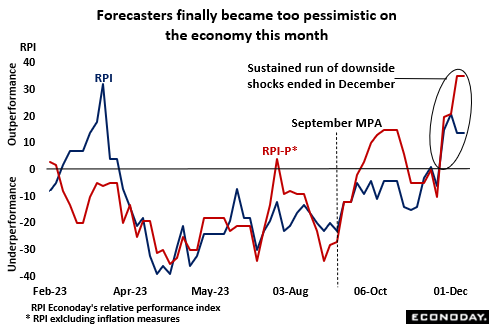

Forecasters have been overly optimistic about the Swiss economy for much of 2023. However, after a protracted period of sub-zero prints, Econoday’s relative performance index (RPI), which measures overall economic activity versus market expectations, moved up into positive surprise territory at the start of December. Even so, recent upside surprises have been largely restricted to the real economy data – crucially, CPI inflation in particular has continued to undershoot.

In summary, there is little pressure on the SNB to revert back to its tightening cycle. Indeed, in current circumstances, the bank would find it very difficult to justify any increase in the policy rate. Still, neither will it want financial markets to get too far ahead of themselves when it comes to possible monetary easing in 2024. As such, the announcement of a steady policy stance is likely to be accompanied by a still moderately hawkish statement.

Econoday’s Global Economics articles detail the results of each week’s key economic events and offer consensus forecasts for what’s ahead in the coming week. Global Economics is sent via email on Friday Evenings.

Econoday’s Global Economics articles detail the results of each week’s key economic events and offer consensus forecasts for what’s ahead in the coming week. Global Economics is sent via email on Friday Evenings. The Daily Global Economic Review is a daily snapshot of economic events and analysis designed to keep you informed with timely and relevant information. Delivered directly to your inbox at 5:30pm ET each market day.

The Daily Global Economic Review is a daily snapshot of economic events and analysis designed to keep you informed with timely and relevant information. Delivered directly to your inbox at 5:30pm ET each market day. Stay ahead in 2025 with the Econoday Economic Journal! Packed with a comprehensive calendar of key economic events, expert insights, and daily planning tools, it’s the perfect resource for investors, students, and decision-makers.

Stay ahead in 2025 with the Econoday Economic Journal! Packed with a comprehensive calendar of key economic events, expert insights, and daily planning tools, it’s the perfect resource for investors, students, and decision-makers.