While the BoE is widely seen lowering interest rates over coming months, there is a clear consensus expecting Thursday’s policy announcement to leave Bank Rate at 5.25 percent, the level to which it was raised back in August 2023. Despite its recent, and surprisingly sharp slowdown, inflation remains well above target and far too high to accommodate any near-term cut in rates. Indeed, there may even be some MPC members who still want another increase – recall that in December, Jonathan Haskell, Catherine Mann and Megan Greene all pressed again for a 25 basis point hike.

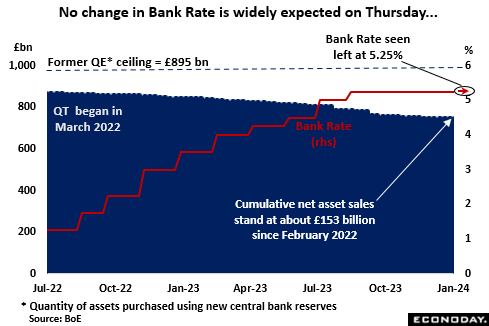

Consequently, the main market focus this week will be on how widely the vote is split with the tone of the policy statement and the minutes watched for any clues about when the first ease might be delivered. A new Monetary Policy Report (MPR) will also be available and might offer some additional insight into the possible timing but its credibility has been badly damaged by sizeable revisions to recent forecasts and investors now pay it only scant attention. Anyway, away from interest rates, policy continues to be made more restrictive by the QT programme which currently seeks to reduce the stock of gilts held in the Asset Purchase Facility (APF) by £100 billion to £658 billion over the year to October 2024. As of late January, net disposals had shrunk outstandings to just over £741 billion, implying a fall in total QE assets of about £153 billion since their peak level in the first quarter of 2022. There is no reason for supposing that the programme will be amended.

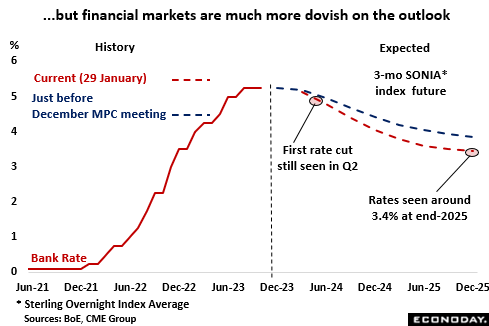

Since December’s MPC meeting, financial markets have become much more dovish on the interest rate outlook. The first cut is still expected next quarter but by the end of the year, 3-month rates are now seen around 4.0 percent, about 40 basis points lower than the level anticipated last time. By the end of 2025, rates are priced at just 3.4 percent.

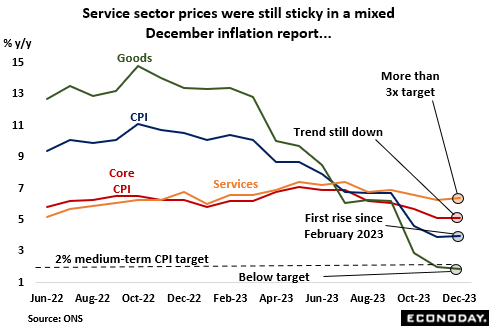

Inflation continues to drive policy and, to this end, the December inflation report was mixed. On the positive side, a minor uptick in the headline rate to 4.0 percent was attributable to the more volatile components and masked a stable core which, at 5.1 percent, remained at its lowest level since February 2022. Moreover, at 1.9 percent, inflation in the goods sector fell below target for the first time in nearly four years. However, less promisingly, the service sector rate – a key measure for the MPC – edged a tick firmer to 6.4 percent, more than three times the target. The relative stickiness of prices here remains a significant hurdle in the path of cutting Bank Rate for a majority of the policymakers. Still, with household energy bills likely to shrink by perhaps 16 percent in April, headline inflation should at least fall sharply next quarter and probably undershoot the current BoE forecast by some margin.

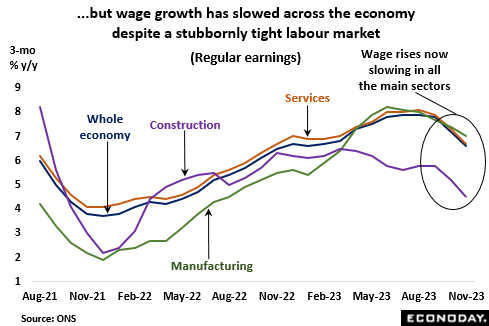

Importantly too, wage growth is now declining across all the main sectors and that despite what would appear to be a still tight labour market (the official labour force survey data remain sidelined due to an inadequate response rate). At 6.6 percent in November, the headline (3-monthly) annual rate for regular earnings matched the lowest since November 2022 and was fully 1.3 percentage points down on its August peak. Manufacturing, construction and, crucially, services, have all posted a marked deceleration and the broad-based nature of the slowdown will be more than well received at the bank. Even so, current rates remain too high to make the inflation target attainable on a sustainable basis meaning that the cooling process has further to go if Bank Rate is to be cut.

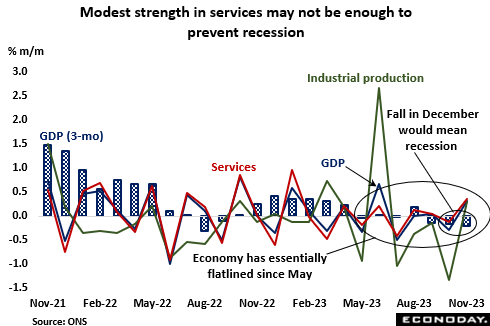

For the real economy, monthly growth of 0.3 percent in November lessened the chance of recession last quarter but with negative revisions to GDP in both August and September, it remains a very real possibility. In any event, according to the latest available hard data, the economy probably at best flatlined from the middle of the year as services expanded just enough to offset persistent weakness in goods production. Domestic demand is soft, notably in the household sector where December retail sales volumes saw their steepest drop since the January 2021 Covid lockdown to hit their lowest level since May 2020.

Leading indicators point to another poor quarter for manufacturing but service sector surveys have been mixed. Hence, while January’s flash PMI (which was overly optimistic for much of 2023) found the strongest rise in business activity in eight months, the CBI remains much more cautious. On the upside, the economy is likely to receive a sizeable boost from the Budget in early March. Ahead of a probable general election later in the year, Chancellor Jeremy Hunt is expected to deliver a package of measures aimed at boosting growth and the government’s lowly standing in the opinion polls. However, any fiscal stimulus that threatens to break the government’s self-imposed borrowing rules would almost certainly dampen the pace at which interest rates are cut.

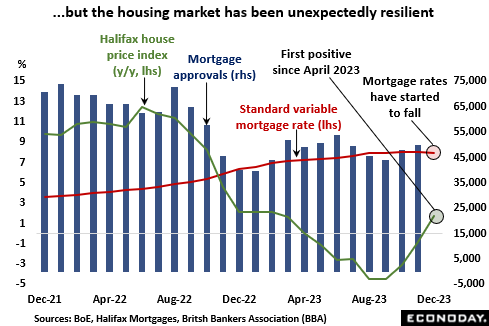

One surprisingly bright spot recently has been the housing market, an important input into household spending plans. According to the Halifax, part of the UK’s largest mortgage lender, average house prices rose in each month of the fourth quarter, thereby ending an unbroken string of declines through September. Indeed, they even ended 2023 some 1.7 percent above their level in December 2022. Crucially, with expectations building for a lower Bank Rate in 2024, mortgage rates are being cut and in November, new buyer enquiries hit their highest mark since May 2022. Approvals are also on the rise. This year is unlikely to see strong demand but the improvement in the housing market was probably a significant factor helping consumer sentiment to climb to a 2-year high this month.

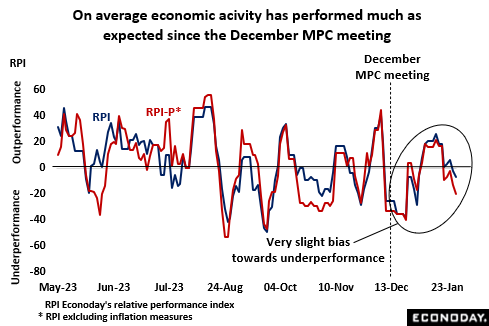

In any event, overall economic activity since the bank’s December deliberations has performed much as expected. Upside surprises in the data have almost matched the downside shocks leaving Econoday’s Relative Performance Index (RPI) averaging minus 3 and its inflation-adjusted counterpart (RPI-P) minus 5. Such readings suggest little additional pressure on the MPC to adjust policy near-term and should be reflected in only limited changes to the bank’s new growth forecasts.

In sum, the BoE has sought in recent weeks to downplay the chances of an early cut in interest rates. It will be more than a little relieved that wage growth is now declining but, with underlying inflation still double the target, it will not want to risk throwing away its hard-won disinflationary gains by easing too soon. Nonetheless, it will be worth keeping an eye on how the MPC votes – any reduction in the hawks’ tally might be read as a signal that the first ease is not too far away.

Econoday’s Global Economics articles detail the results of each week’s key economic events and offer consensus forecasts for what’s ahead in the coming week. Global Economics is sent via email on Friday Evenings.

Econoday’s Global Economics articles detail the results of each week’s key economic events and offer consensus forecasts for what’s ahead in the coming week. Global Economics is sent via email on Friday Evenings. The Daily Global Economic Review is a daily snapshot of economic events and analysis designed to keep you informed with timely and relevant information. Delivered directly to your inbox at 5:30pm ET each market day.

The Daily Global Economic Review is a daily snapshot of economic events and analysis designed to keep you informed with timely and relevant information. Delivered directly to your inbox at 5:30pm ET each market day. Stay ahead in 2025 with the Econoday Economic Journal! Packed with a comprehensive calendar of key economic events, expert insights, and daily planning tools, it’s the perfect resource for investors, students, and decision-makers.

Stay ahead in 2025 with the Econoday Economic Journal! Packed with a comprehensive calendar of key economic events, expert insights, and daily planning tools, it’s the perfect resource for investors, students, and decision-makers.