The US economy is experiencing a variety of shocks coming out of rapid and massive alterations in government at the federal level, sweeping changes to trade and tariff policy, and dislocations in previously allocated federal dollars along with renewing tax cuts to the wealthiest Americans. In the current environment, consumer and business uncertainty are elevated. Anticipation of a recession is increasing. Are recession flags waving? Not quite yet, but the wind seems to be picking up.

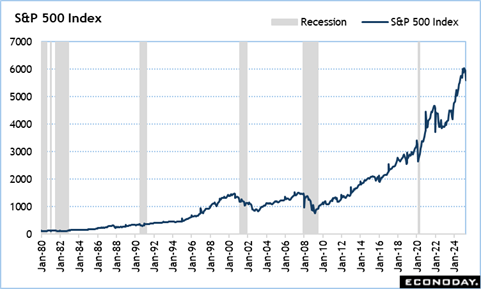

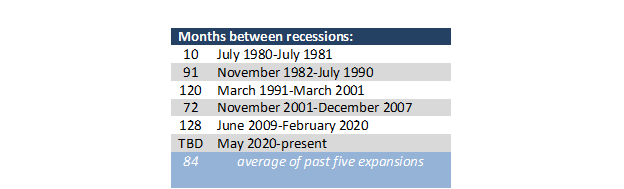

Chair Jerome Powell has said that the Federal Reserve does not have a recession in its forecast, but that the risks for one are greater. The US economy has experienced a long period of growth after the trough of the Great Recession (December 2007 to June 2009) with uninterrupted expansion since then except for the record brief recession associated with the Covid-19 shutdowns (February-April 2020).

Former Fed Chair Janet Yellen has famously said that expansions do not die of old age in reference to the long expansion after the Great Recession and before the pandemic. Former Fed Chair Ben Bernanke added the corollary that they are murdered. The point is that the length of an expansion isn’t necessarily a sign of its imminent demise, rather that expansions end due to exogenous events that severely affect the economy’s smooth functioning and ability to recover from the shock.

The question is if the policies and actions of the Trump administration is going to bring on a recession. The short answer is that it is probably too soon to tell. There are a few indicators that can fairly reliably wave the warning flag.

The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) is the guardian of assigning dates to economic peaks and troughs that demarcate a recessionary period. The NBER defines a recession as “a significant decline in economic activity spread across the economy, lasting more than a few months, normally visible in real GDP, real income, employment, industrial production, and wholesale-retail sales.” It can take them months after a recession has started to make the official call.

Those who watch the economy closely – markets, central bankers, politicians, etc. – can’t wait for the NBER and have to act based on current information. They need some framework for early warning of a downturn and rely on a few rules of thumb for calling a recession. These are:

• Two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth.

• A persistent increase in the unemployment rate of more than 50 basis points from its cyclical low.

• An inverted yield curve.

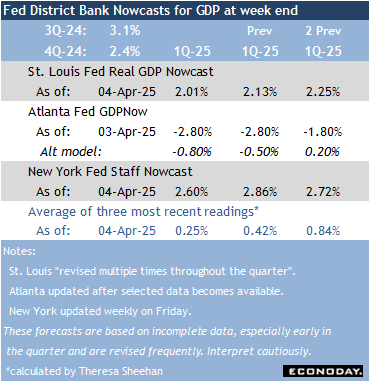

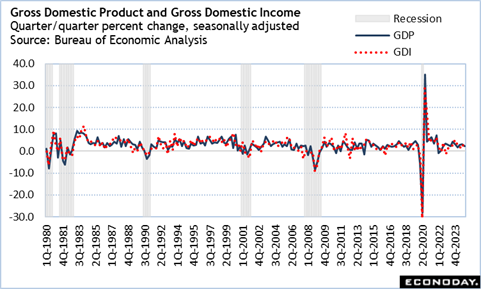

After the wild swings in GDP in the first months of the pandemic in 2020, GDP settled into a nearly unbroken string of quarter with modest-to-moderate expansion through the fourth quarter 2024. That growth appears to be in jeopardy in the first quarter of 2025. Businesses and consumers front-loaded some spending in the fourth quarter 2024 with the looming threat of higher prices related to tariffs. The most accurate of the three Fed district bank GDP Nowcasts points to a contraction in the first quarter 2025. The Atlanta Fed GDPNow forecasts negative 2.8 percent growth in the first quarter. Their model was particularly swayed by the large exports of nonmonetary gold in January and February. Their alternative model excluding that still looks for contraction of 0.8 percent in the first quarter. However, The St. Louis Fed GDP Nowcast is for GDP to rise 2.01 percent and the New York Fed Staff Nowcast is for up 2.6 percent. The advance estimate for first quarter GDP is set for release at 8:30 ET on Wednesday, April 30.

One thing that is a counter to the recession narrative is the performance of gross domestic income (GDI). Note that the NBER doesn’t just look at growth, but also income. If GDI does not weaken, it may suggest that any dip in GDP growth is overstated.

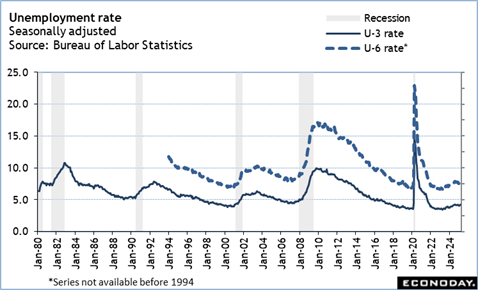

The unemployment rate – or U-3, total unemployed as a percent of the civilian labor force – is the official unemployment rate. However, it is also useful to watch the U-6 rate – total unemployed, plus all people marginally attached to the labor force, plus total employed part time for economic reasons, as a percent of the civilian labor force plus all people marginally attached to the labor force – as the broadest measure of unemployment. A weakening job market tends to affect those who are among the less employable first.

The unemployment rate has plunged from its peak of 14.8 percent in April 2020 to 3.4 percent in April 2023. It slowly and unevenly worked its way back up to 4.2 percent in July 2024. Since then, it has been in a narrow range of 4.0 percent to 4.2 percent. It is too soon to say it is significant, but the U-3 rate has risen from 4.0 percent in January to 4.1 percent in February to 4.2 percent in March. This is only 20 of the 50 basis points that might constitute a louder inflation signal, but if the unemployment rate reaches 4.3 percent or higher in April it is a cause for concern.

More immediately concerning is that the U-6 rate rose fifty basis points in February to 8.0 percent, although it backed down a tenth to 7.9 percent in March. Nonetheless, February and March are the highest readings since 8.2 percent in October 2021.

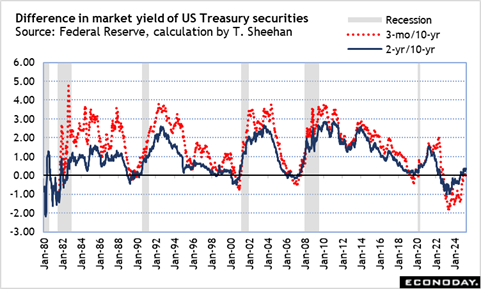

The gap between the 2-year/10-year Treasury yields – which the Fed watches more than the more volatile 3-month bill/10-year note behavior – often precedes a recession. The most recent episode in 2023 was more about the inflation fight at a time of modest-to-moderate expansion. That has lifted toward the end of 2024 and into early 2025. However, the difference in the market yields remains narrow with shorter-term securities more in demand in a time of uncertainty.

There are other indications of a weakening economy that are worth keeping an eye on.

Stock market behavior isn’t normally considered a signal of a recession. Sometimes a sharp drop is a correction or a reaction to short-term events, not a warning. However, it should not be ignored.

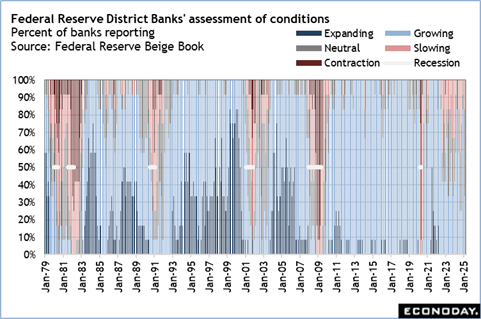

Although the Fed’s Beige Book is not hard data, the anecdotal evidence about economic conditions across the 12 districts is current and an accurate assessment of business and consumer activity. When 7 or fewer districts broadly describe activity as growing, it is a strong possibility that a recession is in the works. An exception has been the period between July 2022 and October 2024 when the economy was still recovering from supply chain disruptions and dealing with inflation even as the labor supply was tight and demand was high. Solid employment kept a recession at bay. The Beige Books released in December 2024 and January 2025 gave every indication that activity was on the rise and the economy was expanding comfortably across the districts. However, the most recent one released in March reflected an abrupt deterioration in conditions from 100 percent of districts reporting at least some growth in the period between late November and early January to only 33 percent in the period between early January and late February. If the next Beige Book set for release on April 23 at 14:00 ET is similar to the prior one, the risks of a recession become noticeably higher.

In the past, there has been a substantial lag between when the NBER announced the turning points in the economy and when these actually occurred. The NBER needs to have all the data and then analyze it thoroughly. Understandably that takes time. However, the data was unmistakable in the first months of the recession brought on by the pandemic. The NBER called the last recession on June 8, 2020 and put the peak for the prior expansion in February 2020. On July 19, 2021, the NBER said the recession lasted a scant two months in March and April 2020.

The short interval between when the NBER determined the recession start/end for the February-March 2020 downturn is probably due to the overwhelming evidence that needed little nuanced interpretation. The present economic data may be much cloudier in terms of accurately assessing whether the US is now in recession. The outlier compared to other downturns is mainly the low unemployment rate.

Econoday’s Global Economics articles detail the results of each week’s key economic events and offer consensus forecasts for what’s ahead in the coming week. Global Economics is sent via email on Friday Evenings.

Econoday’s Global Economics articles detail the results of each week’s key economic events and offer consensus forecasts for what’s ahead in the coming week. Global Economics is sent via email on Friday Evenings. The Daily Global Economic Review is a daily snapshot of economic events and analysis designed to keep you informed with timely and relevant information. Delivered directly to your inbox at 5:30pm ET each market day.

The Daily Global Economic Review is a daily snapshot of economic events and analysis designed to keep you informed with timely and relevant information. Delivered directly to your inbox at 5:30pm ET each market day. Stay ahead in 2025 with the Econoday Economic Journal! Packed with a comprehensive calendar of key economic events, expert insights, and daily planning tools, it’s the perfect resource for investors, students, and decision-makers.

Stay ahead in 2025 with the Econoday Economic Journal! Packed with a comprehensive calendar of key economic events, expert insights, and daily planning tools, it’s the perfect resource for investors, students, and decision-makers.