Following the surprise 50 basis point hike in Bank Rate in June, the BoE MPC is generally expected to revert to a smaller 25 basis point increase this week. However, there is a significant minority of market participants anticipating another 50 basis point move. Crucially, headline and core inflation have decelerated, although current levels of both remain nowhere near the 2 percent target. If the consensus call is correct, what would be a remarkable fourteenth successive tightening would put the benchmark rate at 5.25 percent, matching its highest level since December 2007, and boost the cumulative tightening so far to some 515 basis points in little more than a year-and-a-half. Another split vote is quite likely but note that following the expiration of her second term, one of the MPC’s main doves (and in recent months a regular dissenter) Silvana Tenreyro, was replaced by Megan Greene in early July. Greene, formerly the global chief economist at the Kroll Institute, is likely to be more hawkish than her predecessor and, in any event, will most probably vote with the majority at her first meeting.

In terms of the policy stance, QT is still seen as very much secondary to Bank Rate. However, it continues to run smoothly in the background and remains focused on reducing gilt holdings in the bank’s Asset Purchase Facility (APF) by £80 billion to £758 by the end of September. In the middle of July, disposals stood at nearly £74 billion which, combined with the £20 billion of corporate bond sales already completed, put the total reduction in the balance sheet at about £94 billion. Gilt sales in the current quarter are planned at £2.73 billion, spread evenly across short, medium, and long maturities, and in September the MPC will decide upon the pace of QT for the next 12 months.

In financial markets, interest rate projections have softened slightly compared with just before the June MPC meeting but were especially volatile in the interim. Currently, the peak to 3-month money rates is seen around 5.8 percent but, following the shock jump in inflation in May and subsequent 50 basis point hike in Bank Rate, rates in mid-July were seen climbing as high as 6.5 percent. The ensuing downward adjustment reflects a surprisingly low June CPI but the recent sharp swings in interest rate expectations underline both the sensitivity of investors to inflation developments and the high level of economic uncertainty in general.

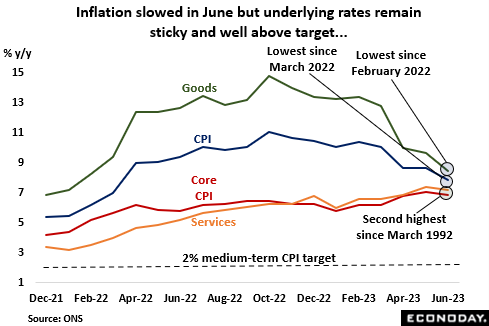

Headline inflation has fallen sharply since topping out at 11.7 percent last October and in June (7.9 percent) posted its lowest reading since March 2022. Moreover, favourable base effects, largely due to weaker energy prices, combined with lower import prices as supply chains flow more freely should see a further marked decline over coming months. However, more importantly, underlying inflation continues to prove a lot stickier and, at 6.9 percent last month, was the second highest since March 1992. Indeed, at its June meeting, the bank said there had been “significant” news suggesting persistently high inflation would take longer to fall. The MPC also noted that the key problem is the service sector where the current rate (7.2 percent rate) is also only just short of a 31-year peak. Inflation in the goods producing sector (8.5 percent) is significantly higher than its services counterpart but has declined fairly consistently and by fully 6.3 percentage points since peaking also in October 2022.

Crucially, although the labour market has started to cool, it is doing so too slowly to have any real impact on wages. The unemployment/vacancies ratio has been edging up since late last year but services in particular are still struggling to find new staff. As a result, whole economy regular earnings growth in the three months to May stood at fully 7.3 percent, a record high outside of the Covid-distorted period. At 7.4 percent and 7.8 percent respectively, the rates in services and manufacturing went one better, chalking up new all-time peaks. In the public sector, regular earnings are rising at a more subdued 5.8 percent but this is still too high to bring the inflation target into sight and future rates here will be supported by the government’s July decision to offer millions of workers a rise of around 6 percent this year.

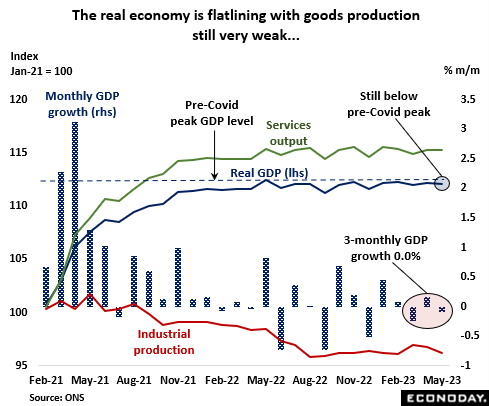

The ongoing tightness of the labour market masks a real economy that has all but stagnated so far in 2023. Real GDP in May was just 0.3 percent above its level last December while quarterly growth was zero. The extra bank holiday for the Coronation of King Charles III on 8 May probably had a negative effect but with some service providers benefitting from increased demand, the net impact is likely to have been minor. Matching the pattern seen across the rest of Europe, goods producing industries continue to struggle with output declining in three of the last four months. According to the CBI, confidence in manufacturing in the July quarter improved for the first time in two years but shrinking order books and declining backlogs hardly bode well. The bottom line is that total output in May was still 0.4 percent below its pre-Covid peak in January 2020 and most leading indicators argue against any significant pick-up near-term. Against this backdrop, further rate increases will inevitably boost the risk of a recession in the second half of the year.

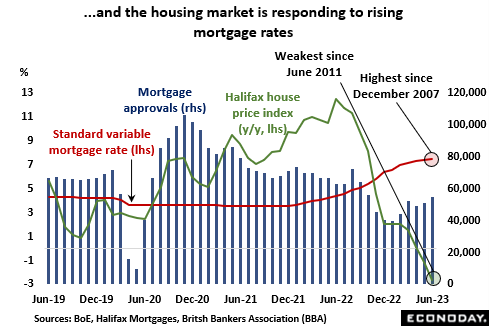

One area where higher borrowing costs are clearly slowing activity and, more obviously, dampening inflation is the housing market. Buyer enquiries have fallen to 8-month lows, mortgage approvals are well down from last August’s peak and, according to the Halifax’s gauge, house price inflation is the lowest in 12 years despite continued limited supply. Moreover, on some estimates, around 800,000 fixed-rate mortgage deals will need to be refinanced between now and the end of the year and a further 1.6 million in 2024. On average, new contracts are expected to cost an extra £2,900 a year. This leaves the housing market in danger of a sharp retrenchment that could add to the downward pressure on consumer spending already posed by tightly squeezed household budgets.

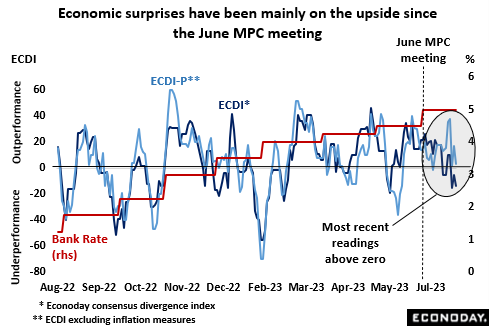

Even so, and despite the BoE’s aggressive tightening, overall economic activity has generally outperformed market expectations since the June MPC meeting. Indeed, although the ECDI (minus 14) has recently slipped below zero, its inflation-adjusted counterpart is still in positive surprise territory as it has been almost continually since the start of June. The unexpected buoyancy here gives the hawks extra ammunition should they want to shoot for another 50 basis point hike.

That said, on current trends GDP will do well to keep its head above water this quarter – all the more so should Bank Rate be raised again on Thursday. However, with underlying inflation stubbornly high, a period of negative growth might well be the fastest route to getting prices back under control. Accordingly, while upcoming CPI reports will inevitably be key, any moderate weakness in the real economy data should not unduly trouble the majority of MPC members. As it is, updated economic forecasts in the bank’s new Monetary Policy Report (MPR) are likely to revise down both growth and inflation but substantial revisions to previous projections have done much to undermine their credibility. Indeed, even the MPC itself now seems to pay them scant attention.

Econoday’s Global Economics articles detail the results of each week’s key economic events and offer consensus forecasts for what’s ahead in the coming week. Global Economics is sent via email on Friday Evenings.

Econoday’s Global Economics articles detail the results of each week’s key economic events and offer consensus forecasts for what’s ahead in the coming week. Global Economics is sent via email on Friday Evenings. The Daily Global Economic Review is a daily snapshot of economic events and analysis designed to keep you informed with timely and relevant information. Delivered directly to your inbox at 5:30pm ET each market day.

The Daily Global Economic Review is a daily snapshot of economic events and analysis designed to keep you informed with timely and relevant information. Delivered directly to your inbox at 5:30pm ET each market day. Stay ahead in 2025 with the Econoday Economic Journal! Packed with a comprehensive calendar of key economic events, expert insights, and daily planning tools, it’s the perfect resource for investors, students, and decision-makers.

Stay ahead in 2025 with the Econoday Economic Journal! Packed with a comprehensive calendar of key economic events, expert insights, and daily planning tools, it’s the perfect resource for investors, students, and decision-makers.