One of the main themes of the July 2024 semiannual monetary policy testimony was the need for the Federal Reserve to remain an independent central bank against the not-so-subtle subtext that US central bankers need to stay out of the political fray. Fed Chair Jerome Powell voiced his certainty that Fed independence – along with independent central banks in other major economies – has been a contributor to growth and financial stability in periods of normality and a bulwark against collapse in times of crisis.

Powell was also adamant that Fed policymakers must set interest-rate and balance-sheet policy according to the best available data to achieve the dual mandate of maximum employment and price stability.

Generally, this assertion – by Powell or any past Fed Chair – isn’t blatantly challenged. Yet in the current political climate, the veracity of that claim is likely to be treated with skepticism in some public rhetoric. Any rate move in proximity to national elections can be construed as having a political impact. While it would be naïve to say that Fed policymakers are blissfully unaware of politics, it is fair to say that their decision making is focused on the economy and the dual mandate.

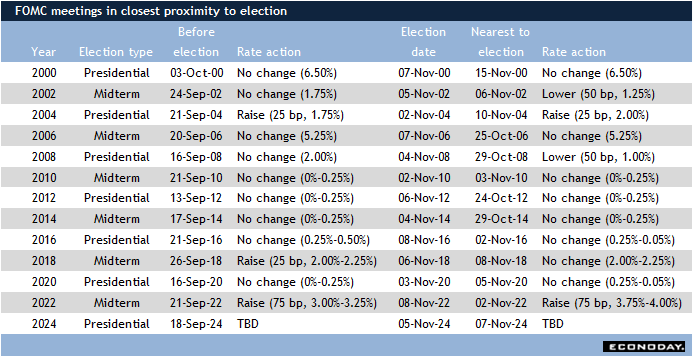

The FOMC meets eight times a year at roughly 7-8 week intervals. It just so happens that the 6th and 7th meetings of the year fall within the final weeks of election season. Sometimes the normal Tuesday start of the two-day FOMC meeting is the same day as election day, as it is this year. In this case, the FOMC will shift the meeting to a Wednesday start to avoid any perception of political bias.

With the current crop of economic data showing a cooler labor market and a resumption of disinflation, it is reasonable to expect that the FOMC is going to be thinking more positively about cutting the fed funds target rate from the 5.25-5.50 percent range where it has been since July 2023. The next FOMC meeting is July 30-31, but that is probably too soon to expect the first change in the fed funds rate. The FOMC is being cautious and patient, and will want another data point or two before loosening policy. The US economy remains in mild expansion, the labor market is healthy, and inflation is healing while inflation expectations are well anchored for the medium term.

This puts the stronger possibility of a rate cut at the September 17-18 meeting, and, if the data continues favorable, for another at either the November 6-8 meeting, or more likely the December 17-18 meeting.

Whether or not the FOMC cuts rates in the coming months, Fed policymakers are going to work to get out the message that monetary policy is data dependent and that they are independent in implementing it. History indicates that the FOMC rarely changes interest rates during national election seasons, and when it does happen, it is usually — but not always — the result of a crisis like the period of the Great Recession (December 2007-June 2009) or in response to elevated inflation in the second half of 2022.

Econoday’s Global Economics articles detail the results of each week’s key economic events and offer consensus forecasts for what’s ahead in the coming week. Global Economics is sent via email on Friday Evenings.

Econoday’s Global Economics articles detail the results of each week’s key economic events and offer consensus forecasts for what’s ahead in the coming week. Global Economics is sent via email on Friday Evenings. The Daily Global Economic Review is a daily snapshot of economic events and analysis designed to keep you informed with timely and relevant information. Delivered directly to your inbox at 5:30pm ET each market day.

The Daily Global Economic Review is a daily snapshot of economic events and analysis designed to keep you informed with timely and relevant information. Delivered directly to your inbox at 5:30pm ET each market day. Stay ahead in 2025 with the Econoday Economic Journal! Packed with a comprehensive calendar of key economic events, expert insights, and daily planning tools, it’s the perfect resource for investors, students, and decision-makers.

Stay ahead in 2025 with the Econoday Economic Journal! Packed with a comprehensive calendar of key economic events, expert insights, and daily planning tools, it’s the perfect resource for investors, students, and decision-makers.