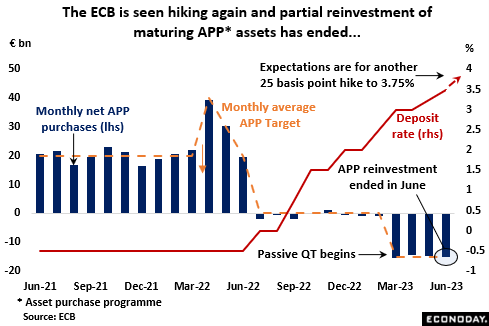

If the June policy announcement and subsequent official comments are anything to go by, ECB tightening is not over yet. The market consensus is for yet another 25 basis point increase on Thursday that would put the deposit rate at 3.75 percent, matching its October 2000 record high, the refi rate at 4.25 percent and the rate on the marginal lending facility at 4.50 percent. It would also boost the cumulative tightening to an unprecedented 425 basis points in just a year. That said, with the likes of even Dutch central bank President Klaas Knot, an arch-hawk on the Governing Council (GC), now suggesting that underlying inflation could have peaked, this week’s move might just be the last in the current cycle.

There has still been no discussion about outright asset sales (active QT) but to accelerate the pace at which its balance sheet will shrink, from the start of this month the ECB ended partially reinvesting maturing assets acquired under the asset purchase programme (APP). Through the end of June, disposals were around €68 billion, mainly reflecting a €54 billion fall in holdings under the public sector purchase programme (PSPP). To date, the pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP) has been untouched by QT and full reinvestment here is currently still scheduled to run until at least the end of next year. However, at €1.713 trillion in June, the PEPP was providing a substantial amount of liquidity that at least some GC hawks will no doubt want to see reduced.

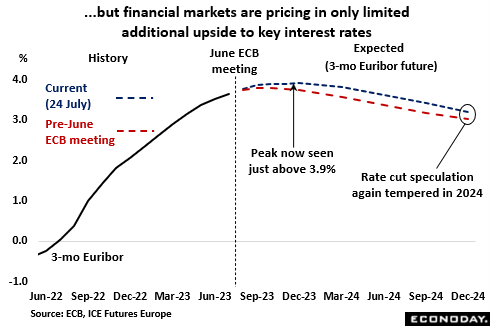

Since the June meeting, financial markets have become a little more aggressive on their outlook for interest rates but, if correct, the peak is well within sight. The top to 3-month money rates is now put at about 3.9 percent, up from 3.8 percent previously but still well short of the near-4.1 percent level priced in just before the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) back in March. Rates are also expected to remain around 20 basis points higher than anticipated last month throughout 2024, finishing the year close to 3.2 percent.

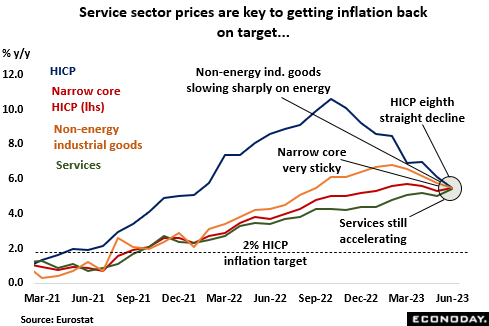

Recent inflation developments have been mixed but, ultimately, still far too strong. The headline rate has continued to fall and, at 5.5 percent in June, was the lowest since January 2022 and down more than 5 percentage points from last November’s 10.6 percent peak. However, while inflation in the goods producing sector has tumbled, in services it remains on an upward trend, reaching a record high of 5.4 percent just last month. Strong price gains here are key to what are still stubbornly sticky underlying rates, notably the HICP narrow core which, at 5.5 percent in June, was just a couple of ticks short of its all-time peak.

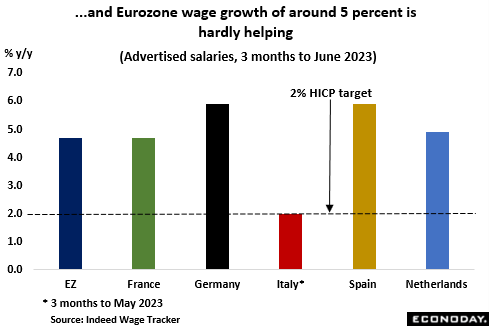

In the main, household inflation expectations have eased a little further since the June meeting and wage growth in at least some Eurozone countries has shown tentative signs of topping out. Even so, the Indeed Wage Tracker that the central bank follows closely still shows a tight labour market helping to keep salary rates well above those consistent with meeting the inflation target. In particular, the latest data for the June quarter had German earnings climbing by almost 6 percent on the year. Some clear deceleration here will be vital to putting a lid on ECB interest rates. That said, the bank has been paying special attention to corporate profits which it currently sees as an even more important factor in overshooting inflation. Rather than simply passing on higher costs, companies’ pricing policies in the aggregate seem to have been more aggressive with firms raising charges by enough to widen profit margins. On its own calculations, the ECB believes that around 60 percent of the (record) 6.2 percent annual increase in the first quarter Eurozone GDP deflator was attributable to rising unit profits. To this end, the bank has warned that without a shift in corporate behaviour key interest rates will have to stay higher for longer (a view shared by the IMF).

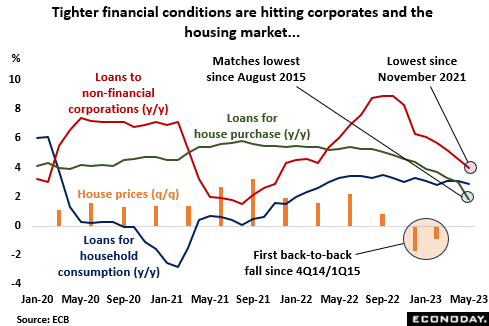

In broad terms, the real economy is moving sideways as modest gains in services offset persistent weakness in manufacturing. Increasingly restrictive financial conditions (the ECB’s new lending survey due tomorrow should highlight this) are clearly hitting the more interest rate sensitive sectors. Growth of lending to non-financial corporations has slowed to its weakest rate since November 2021, in the midst of the Covid crisis, while borrowing for house purchase is increasing more slowly than at any time since August 2015. Indeed, house prices posted outright declines in both the fourth quarter of last year and the first quarter of this, the first back-to-back drop in eight years. In contrast to the last couple of quarters, real GDP may just about have kept its head above water in April-May but most leading indicators argue against any significant near-term improvement. Even so, with the unemployment rate at a record low, sluggish economic activity is not something that will worry the central bank.

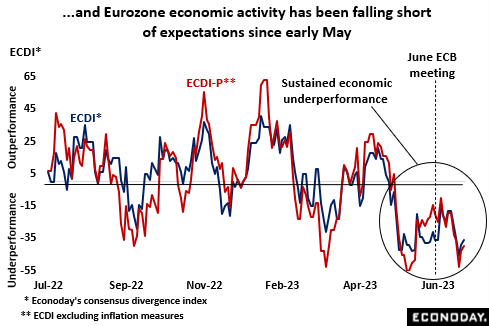

To be sure, the Eurozone economic activity in general has been disappointing investors for some time. Econoday’s consensus divergence index (ECDI) has been sub-zero since early May, showing that forecasters have been consistently too bullish. Moreover, since the ECB’s June meeting underperformance has been particularly marked. Negative readings will not distract a central bank so focused on tackling overshooting inflation but they should bolster the chances that a trend decline in core inflation is not too far away.

In sum, another 25 basis point hike this week looks nailed on and until underlying inflation declines more significantly, the ECB is likely to retain a tightening bias. To this end, the performance of the services sector will be key and the central bank will be following developments here even more closely than usual. Even so, with tentative signs that wage and price pressures are beginning to ease, additional upside to key interest rates would seem only limited.

Econoday’s Global Economics articles detail the results of each week’s key economic events and offer consensus forecasts for what’s ahead in the coming week. Global Economics is sent via email on Friday Evenings.

Econoday’s Global Economics articles detail the results of each week’s key economic events and offer consensus forecasts for what’s ahead in the coming week. Global Economics is sent via email on Friday Evenings. The Daily Global Economic Review is a daily snapshot of economic events and analysis designed to keep you informed with timely and relevant information. Delivered directly to your inbox at 5:30pm ET each market day.

The Daily Global Economic Review is a daily snapshot of economic events and analysis designed to keep you informed with timely and relevant information. Delivered directly to your inbox at 5:30pm ET each market day. Stay ahead in 2025 with the Econoday Economic Journal! Packed with a comprehensive calendar of key economic events, expert insights, and daily planning tools, it’s the perfect resource for investors, students, and decision-makers.

Stay ahead in 2025 with the Econoday Economic Journal! Packed with a comprehensive calendar of key economic events, expert insights, and daily planning tools, it’s the perfect resource for investors, students, and decision-makers.