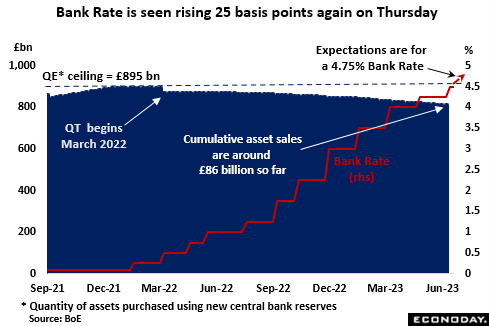

Stubbornly high inflation and accelerating wage growth would seem to leave the BoE with little choice but to hike Bank Rate for what would be a thirteenth consecutive meeting on Thursday. The market consensus is another 25 basis point increase that would put the benchmark rate at 4.75 percent, its highest level since April 2008 and boost the cumulative tightening to some 465 basis points in just a year-and-a-half. In recent meetings, the MPC’s two main doves, Swati Dhingra and Silvana Tenreyro (the latter’s last meeting), have dissented in favour of no change but they may struggle this time to justify keeping rates on hold. Indeed, there must also be a chance that at least one of the hawks will want a more aggressive 50 basis point move.

QT has continued to run smoothly and the planned £80 billion reduction to £758 billion in gilt holdings in the bank’s Asset Purchase Facility (APF) by November remains on track. Earlier this month, bond holdings stood at £808.4 billion. At the same time, the stock of corporate bonds has also been reduced by more than 95 percent from just over £20 billion to slightly under £1.0 billion, essentially concluding the programme earlier than originally planned. The bank has already indicated that it will retain just a small number of very short-term maturity bonds through April 2024.

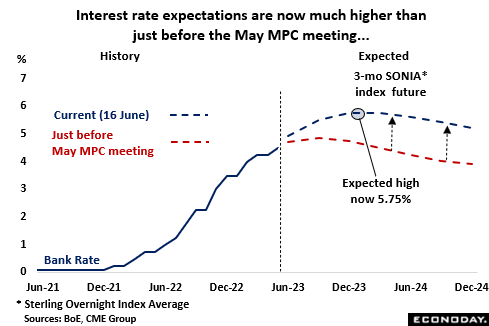

Meantime, expectations for where Bank Rate might top out continue to be ratcheted up, and significantly so. Just before the May MPC meeting financial markets were pricing in a peak to 3-month money rates of about 4.85 percent in September. Investors also seemed confident that the BoE would be lowering key rates over much of 2024 and anticipated a sub-4 percent level by the end of the year. However, new concerns that policy is not tight enough have boosted the expected high to fully 5.75 percent this December and no official cut is seen until around the middle of 2024. Indeed, concerns that the policymakers have been too slow to act on inflation helped gilt yields last week to rise above the levels seen just after September’s disastrous mini-Budget.

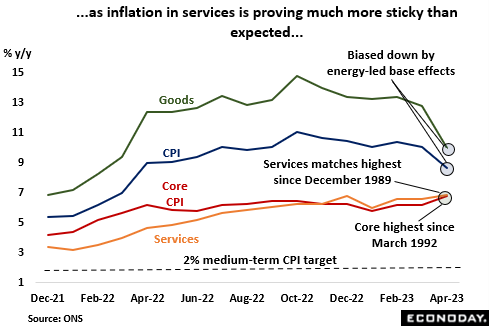

Crucially, inflation is still not behaving itself and the bank is having real problems explaining why. In testimony before the House of Commons Treasury select committee last month Governor Andrew Bailey admitted that the bank’s forecasting model was not working and that the MPC had downgraded its input in policy decisions. The April CPI data were particularly bad. Headline inflation fell sharply, from 10.1 percent in March to 8.7 percent, but this simply reflected strongly negative base effects caused by the hike in energy prices a year ago (a new lower price cap introduced by the energy regulator OFGEM will also help to reduce the overall rate from July). Much more importantly though, the core rate in April jumped from 6.2 percent to 6.8 percent, a level not seen in more than three decades. At the same time, at 6.9 percent, inflation in services climbed to its highest mark since December 1989. In other words, not only is the underlying rate still historically very high, but the trend also remains in the wrong direction.

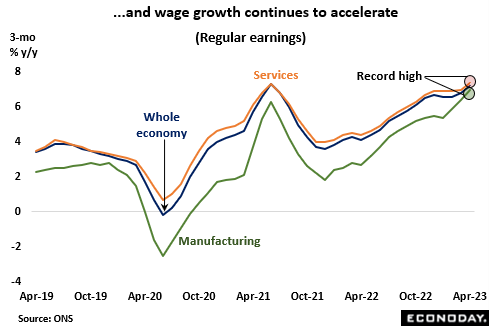

To this end, wages remain a real problem with pay growth climbing at a rapid and accelerating rate right across the economy. In the three months to April, average annual growth of regular earnings in services stood at fully 7.4 percent (in financial services some 9.2 percent), just a tick above its manufacturing counterpart. Both readings were new record highs. For the economy as a whole, the rate was 7.2 percent, only 0.1 percentage point below the Covid-distorted peak seen in June 2021. Indeed, the single month rate was some 7.5 percent. Such values are completely inconsistent with the 2 percent CPI target and underline the ongoing tightness of the labour market. They also in part reflect successful and quite widespread industrial action.

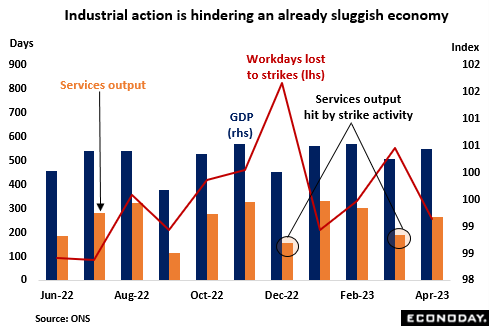

In fact, strike activity looks to have had a particularly significant impact on services. Sizeable monthly declines in the sector’s output in both December 2022 and March this year coincided with steep increases in working days lost. That said, while the economy is clearly very sluggish, first quarter GDP (0.1 percent) at least expanded and the BoE has adjusted its growth forecast for 2023-2025 sharply higher. The deep and protracted recession shown in the February Monetary Policy Report (MPR) has been revised away and in three years’ time total output is now expected to be some 2.25 percent higher. If nothing else, this makes raising Bank Rate again this week politically a little easier to sell. Even so, business surveys still point to the current quarter being another poor period for growth with household spending in particular likely to be weighed down by the high cost of living and rising borrowing costs.

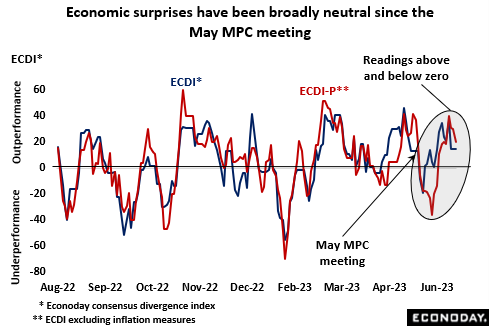

Since the May MPC meeting, surprises in the economic data have been reasonably balanced – the UK’s ECDI and ECDI-P have averaged 12 and 9 respectively over the period. However, both measures have been consistently above zero throughout June and the April CPI report was much stronger than the market (and bank) expected. This outperformance should help to limit worries about the potential damage that another policy tightening might do to the more interest rate sensitive sectors.

In sum, with its economic models broken, Bank Rate already hiked 440 basis points but inflation as persistent as ever, the MPC this week will no doubt be scratching its collective head over what it should do next. Another hike in rates would appear unavoidable if only as a prop to the bank’s dwindling anti-inflation credibility but a consensus 25 basis point increase could well be too small to satisfy financial markets for long.

Econoday’s Global Economics articles detail the results of each week’s key economic events and offer consensus forecasts for what’s ahead in the coming week. Global Economics is sent via email on Friday Evenings.

Econoday’s Global Economics articles detail the results of each week’s key economic events and offer consensus forecasts for what’s ahead in the coming week. Global Economics is sent via email on Friday Evenings. The Daily Global Economic Review is a daily snapshot of economic events and analysis designed to keep you informed with timely and relevant information. Delivered directly to your inbox at 5:30pm ET each market day.

The Daily Global Economic Review is a daily snapshot of economic events and analysis designed to keep you informed with timely and relevant information. Delivered directly to your inbox at 5:30pm ET each market day. Stay ahead in 2025 with the Econoday Economic Journal! Packed with a comprehensive calendar of key economic events, expert insights, and daily planning tools, it’s the perfect resource for investors, students, and decision-makers.

Stay ahead in 2025 with the Econoday Economic Journal! Packed with a comprehensive calendar of key economic events, expert insights, and daily planning tools, it’s the perfect resource for investors, students, and decision-makers.