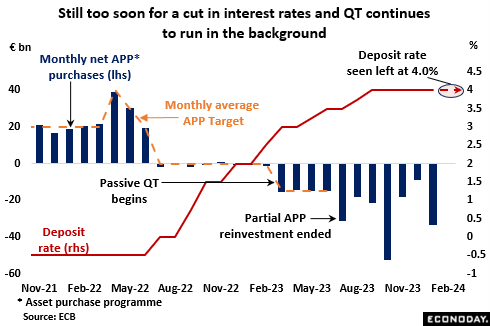

At the ECB’s January meeting, there was a unanimous decision to leave key interest rates on hold and forecasters anticipate the same neutral outcome this week. Thursday’s announcement is widely expected to leave the deposit rate at its 4.0 percent record high while the refi rate stays at 4.50 percent and the rate on the marginal lending facility at 4.75 percent. However, recent comments from Governing Council (GC) members show a widening split over how soon key rates should be lowered. For now, most would seem to prefer to wait for more data, crucially on underlying inflation and wages, but the more dovish policymakers are clearly eyeing a cut sooner rather than later. Just a couple of weeks ago, Bank of Greece Governor Yannis Stournaras was calling for a move no later than June despite policy supposedly being data dependent. Still, such disagreements are only to be expected as a major shift in policy approaches and, to this end, investors will be watching especially closely the bank’s updated inflation forecast for clues about how far rates might be lowered in 2024.

For now, QT remains restricted to the asset purchase programme (APP) where net sales in excess of €33 billion in January boosted cumulative disposals since last February (when partial reinvestment was introduced) to almost €260 billion. This left the remaining QT stock at €2.99 trillion, the lowest level since April 2021. The pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP) will not be brought into the QT fold until July with a monthly target of €7.5 billion for net sales through December. Liquidity in 2024 will also be drained by the expiration of the final targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTRO-III).

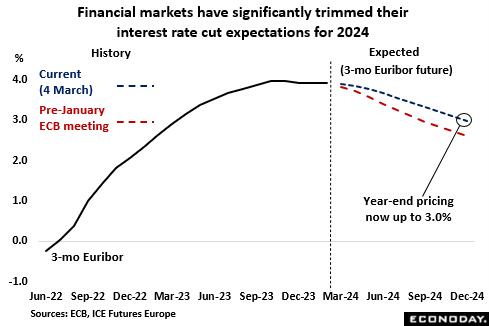

Since its meeting at the end of last year, the ECB has made a good job of tempering speculation in financial markets about the likely pace of cuts in key interest rates in 2024. From currently nearly 3.95 percent, futures prices now put 3-month Euribor at 3.00 percent in December, some 40 basis points higher than implied just before January’s policy deliberations.

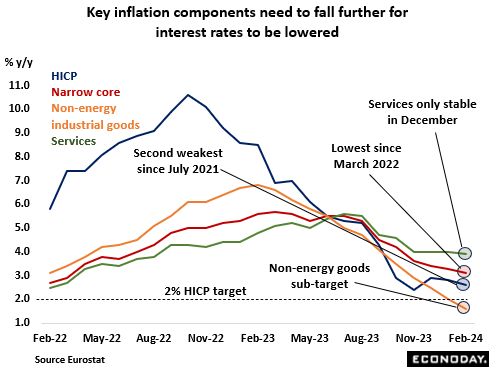

As it is, better news on inflation is needed to open the door to any easing. The provisional February HICP data extended the solid trend decline in the Eurozone’s headline annual rate that began in late-2022 and the key underlying rates also decelerated further. Non-energy goods inflation even fell well below 2 percent. However, at 3.1 percent the narrowest core was still more than a full percentage point above target and, of particular importance to the ECB, inflation in services was still almost 4 percent. In fact, the service sector rate has hardly moved since November and what happens here will have a big say in the overall inflation profile over coming months.

In December, the ECB expected headline inflation to fall from what was then 2.4 percent to 1.9 percent at the end of the forecast horizon in 2026, just undershooting the 2 percent target. However, it also saw the core rate at 2.1 percent, and so slightly above. This provided the fundamental justification for keeping policy on hold. The cut-off date for this quarter’s updated forecast was probably too early to include the flash February data but it may be that the core rate will now be shown on, or even below, target. If so, that would significantly bolster easing speculation.

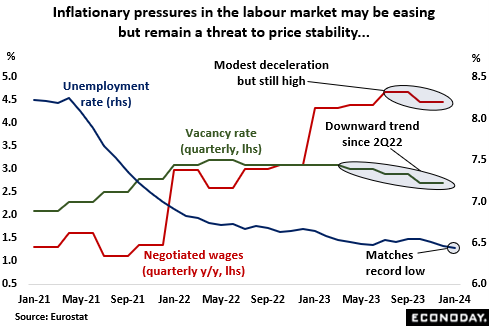

Still, the labour market remains a major hurdle in the path of lower official interest rates. Vacancies have been trending down since the middle of 2022, suggesting a clear cooling in the demand for new workers. However, at 6.4 percent in January, the jobless rate matched its record low and the apparent scarcity of potential new hires has kept businesses very reluctant to shed staff. Indeed, this is almost as true of Germany, to all intents and purposes now in recession, as it is of the stronger Eurozone economies. This means that the ECB is tracking wage developments especially closely and here the latest data have been only cautiously optimistic. Hence, negotiated wages were growing at an annual 4.5 percent rate at the end of 2023, down from the previous quarter’s record 4.7 percent but, for the inflation target, dangerously high at a time when productivity is declining. This means that firms may have to take a bigger hit to profit margins if inflation is to fall back to target within an acceptable timeframe.

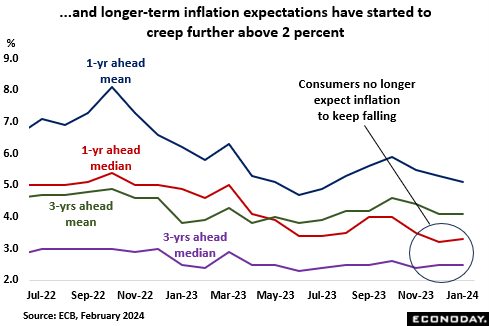

Inflation expectations continue to have a big impact on the bank’s policy decisions and recent data have been similarly mixed. Versus December, the ECB’s own survey found consumers in January anticipating a slightly higher inflation rate in three years’ time, the median call (2.5 percent) rising for a second straight month. More optimistically, the EU Commission’s February report recorded falls in expected selling prices in both manufacturing and services but also noted that the rate in the household sector jumped to its highest level since last March. With the 2024 wage negotiations currently underway, this increase may well ring a few alarm bells at the bank.

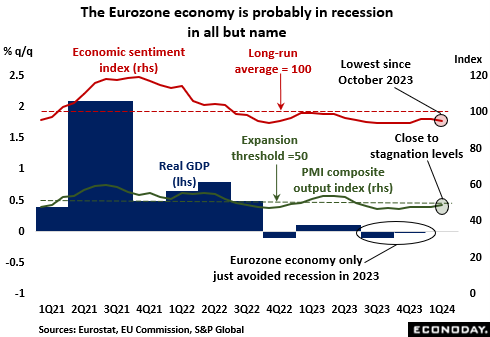

In terms of the real economy (and subject to revisions), the Eurozone avoided recession in the second half of last year. However, it only did so by virtue of zero growth in the final quarter of the year and early data on the current quarter have signalled minimal, if any, improvement. Industrial production has not seen positive quarterly growth since July-September 2022 with output in Germany currently at its weakest level since Covid-impacted May 2020. Services continue to hold up better but with retail sales volumes in December at their lowest since April 2021 and consumer confidence still soft in February, the outlook for household spending in general is anaemic at best. Taken together with sluggish world trade, the signs are that the Eurozone economy will continue to struggle over the first half of the year.

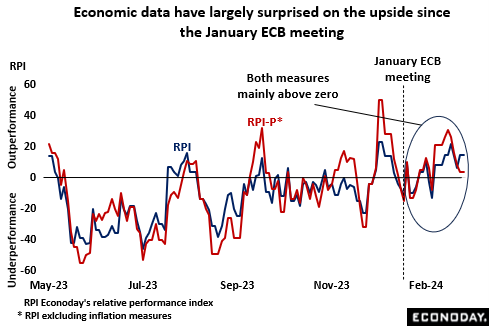

Even so, since the January ECB meeting, typically subdued economic data have still generally come in a little stronger than expected. Econoday’s relative performance index (RPI) averaged 6 over the period and its inflation-adjusted counterpart (RPI-P) 9. Both readings show market predictions slightly biased to the downside, albeit more with regard to the real economy than prices. Even so, the magnitudes are small enough to suggest that there will be no major change to the bank’s December GDP forecast.

The minutes of the January ECB meeting showed that the majority of GC members saw more risks in easing too early than too late. Having won back at least some credibility on the back of the slide in inflation since late in 2022, the bank is desperate not cut interest rates only to have to raise them again should inflation re-accelerate. This increases the likelihood that, despite probable calls from the doves for an earlier move, policy will stay on hold until at least May. That said, if the new forecasts show inflation below target by the end of the projection horizon, financial markets will no doubt be contemplating a cut as soon as April.